|

|

||

|

Death Stacks A board game for two players Copyright © 2004

Invented by Stephen Euin Cobb --- Author,

Columnist, Magazine Writer, Award-Winning Podcaster ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Object of the game: Win by capturing all your opponent’s pieces.

Items Needed

One ordinary checkerboard with its usual set of checkers (twelve red and twelve black). Some people find it more practical to use poker chips since they are thinner and better designed to stack.

The Board’s ‘field of play’

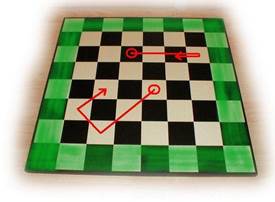

In Death Stacks, all the squares around the outer edge of the board are called “wall squares” because they form a contiguous wall around the field of play. (See photo.) No piece can ever be placed on a wall square. Play is confined to the central 36 squares, which are called “zone squares,” or collectively: “the zone.”

Setting up the Board to Begin the Game

Place the board on a table normally. Each player fills all six squares of their home row with stacks of two checkers each. Play alternates with each player taking one turn.

Rules for Moving

The number of pieces in a stack determines the distance the stack moves. A stack three pieces high must move exactly three spaces—not more than three, and not less than three. Likewise, a four-stack must move exactly four spaces; a two-stack must move two; and a single piece all by itself (a one-stack) moves only one space.

Moves can be made forward, backward, left, right, or along any diagonal line.

Moves are not blocked by stacks that happen to be sitting in the path of the move.

All moves are done in a straight line unless the move would extend into or through one or more walls, in which case the path of that move is reflected by the wall like a mirror. Thus, no matter how long a move is, its entire path will always remain in the zone. (The two example moves shown in the photo both involve four-stack moves, and so, moves of four spaces.)

Stacking

A stack belongs to the player whose piece is on its top. Thus, capturing an opponent’s stack (of any height) is done by placing one of your stacks (of any height) on top of it.

Captured stacks are never removed from the board. All captured pieces become part of the stack they are in and must be included in the count of pieces in that stack.

If you wish, you may use your turn to place one of your stacks (of any height) on top of another one of your stacks (of any height).

A stack may contain any mixture of yours and your opponent’s pieces, but the arrangement and order of pieces within a stack cannot be altered except by continued stacking and restacking.

Breaking Stacks Apart

During your turn, you have the option of moving one of your stacks or only a portion of its top. This top portion may include any number of pieces (be they yours or your opponent’s) and may leave behind a stack also composed of any number of pieces (yours or your opponent’s).

When breaking stacks apart, the distance to be moved is determined not by the size of the stack of origin, but by the size of the stack that is actually in motion. (For example: if moving two pieces from the top of a four-stack the distance moved is two, not four.)

If you capture a stack containing one or more of your lost pieces, your subsequent moves may be used to liberate those pieces by unstacking this stack to a height where one or more of your formerly lost pieces tops a newly freestanding stack.

The Too-Tall Rule (New for 2005)

There

is no limit to how tall a stack can be at the end of your turn.

However, if, at the beginning of your turn, any of your stacks is taller than

four pieces you must use your current turn to reduce the too-tall stack to

four pieces or less. The stack in motion (which you remove from atop the

too-tall stack) is governed by the normal rules, and may contain any number

of pieces without limit. Failure to comply with the Too-Tall Rule will cost

you one turn--but only if your opponent points out your offence before

completing his next turn. The Repeating

State Rule (Added in 2015 at the recommendation of Joe Blevins and

others at ConCarolinas) If the arrangement of pieces on the board returns to exactly the same state for a third time, the game is over and neither player wins. The three identical states need not be produced by consecutive moves. The End.

Death Stacks Copyright © 2004 by Stephen Euin Cobb |